Once widespread in the mountain tributaries of the Pearl, Yellow, and Yangtze Rivers in central/southern China, Chinese giant salamanders are now Critically Endangered. Since the 1950's, giant slamander populations have decreased 80% with the main population stressors being overharvest, habitat loss, and water pollution. The Chinese government even listed the species as a class II protected species in 1989 which prohibits the take of wild individuals. Chinese giant salamanders are valuable for their meat and other body parts and, because of that, poaching remains a high threat against the species to the point where some experts predict the species could go extinct in the wild in the next few decades.

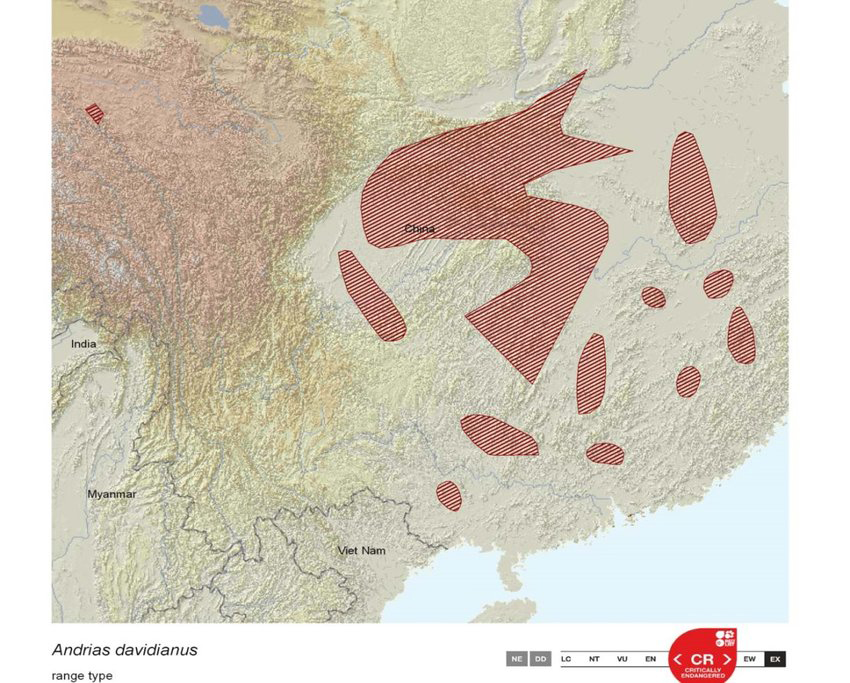

The current distribution (red shading) of the Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus; (IUCN 2010). The location on the high plateau to the far left of the figure may now be uninhabitable by A. davidianus (Pierson et al. 2014).

The current distribution (red shading) of the Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus; (IUCN 2010). The location on the high plateau to the far left of the figure may now be uninhabitable by A. davidianus (Pierson et al. 2014).

This video was produced by the Ocean Park Conservation Foundation intern students that visited the Chinese giant salamander project and its study site. OPCF’s University Student Sponsorship Program (USSP) aims to encourage the next generation of students to consider a career in conservation by giving them a chance to experience a real-life conservation job in the field.

Captive breeding and reintroduction are a viable strategy often implemented to aid recovery efforts, although several pieces of information are needed to make such a method effective. Currently, a huge farming industry for captive breeding of Chinese giant salamanders has developed to meet consumer demand for meat, but breeding in smaller farms is often difficult and wild individuals are still captured to supplement these smaller facilities [CSIS, 2009; Gang et al., 2004; UNEP-WCMC, 2008; Wang et al., 2004; Xie et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2002].Fortunately, in order to become certified by the government for the legal sale of salamander meat, farms must release a portion of their animals back into the wild to support conservation and population growth. These reintroductions are typically coordinated by the provincial Fisheries Department and individual breeding farms; however, the burden of monitoring these released animals is the responsibility of scientists associated with regional Universities and Research Institutes. The conservation physiology lab aids in the important task of evaluating different aspects reintroduction and monitoring including post-release survival, habitat use, and movement. For more information about the Chinese Giant Salamander, please click on the link below and watch the video!

We are evaluating the movements of released salamanders and the properties of both the water and terrain of the areas that the released salamanders choose as habitat. We are using two different mark-recapture methods to track salamanders post-release. The first method uses Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tags implanted on the tails of salamanders. The PIT tags allow for identification of recaptured animals, so that dispersal rates, movement patterns, and range expansions of salamanders (as well as their growth and development) can be measured. In addition, an in-stream drift fence with electronic readers allows our researchers to capture information on which PIT tagged animals pass through the fence at what time. For the second method, we are using radio-transmitters implanted into the body cavity of salamanders. These allow our researchers to monitor the migration of these animals on a weekly basis without recapture. We are also marking both release and recapture sites with a global positioning system (GPS) to track distances traveled.

After recapture of released salamanders, we are collecting data about the recapture site such as the elevation, slope, terrain, stream width, stream depth, forest structure, topography, canopy cover, stream substrate, size of cover used for hiding, and the distance to human influences. These data are being used to develop a model of habitat that is selected for and against by giant salamanders released into the wild. We are also measuring specific water variables of stream sites that salamanders are recaptured from, such as temperature, pH, salinity, flow rate, dissolved oxygen, dissolved solids, turbidity, and conductivity. This information is being used to predict salamander migration as well as improve the water conditions in captive breeding facilities.

The conservation physiology lab collects information on the reproductive ecology of the Chinese giant salamander in captivity. We are collecting data such as age and date of first mating, the number of animals breeding at different breeding farms, egg and sperm concentration across seasons and in response to water temperature, fertilization rates, embryo development, and the effect of flow through streams vs. farms without flow streams. We are also recording the success rate of artificial fertilization techniques.

We are surveying for the presence of chytrid fungus and ranavirus disease in Chinese giant salamander hatcheries, in wild populations, and in pre-release animals in order to establish infrastructure of resources to monitor and study the rapidly spreading ranavirus that is killing hundreds of salamanders in the Shaanxi Province. This information is being used to determine animals safe for release as well as the overall prevalence of the disease in captive populations that may affect production.

Stay tuned for Research Updates!

The Chinese giant salamander studies described herein are conducted in partnership with the Shaanxi Institute of Zoology. This partnership was established in 2009 in order to monitor Chinese giant salamanders released into Shaanxi Province between 2010 and 2015. The interdisciplinary nature of the project fosters teaching and learning environments by collaborators at all levels while broadening graduate students’ encounters among various disciplines and careers. Moreover, international exchanges of junior investigators and students between the U.S. and China (e.g. Mississippi State University) provides valuable experiences for students early in their professional careers. This project represents a positive model for the conservation of China’s aquatic ecosystems that works with local industry, and we hope that this will serve as an example to inspire other conservation initiatives across China.

These studies are funded by the US Forest Service International Programs (IP), Asia Pacific Office. The US Forest Service (IP) promotes sustainable forest management and biodiversity conservation internationally. By linking the skills of the field-based staff of the US Forest Service with partners overseas, the Agency can address the most critical forestry issues and concerns. The Asia Pacific region encompasses vast diversity--in forest type, culture and level of economic development--in addition to critically high population densities. The region hosts some of the most important biodiversity as well as some of the most threatened natural resources in the world. For the United States, our Pacific neighbors are crucial partners--for trade, environment and regional stability. www.fs.fed.us/global/globe/asia/welcome.htm

These studies are funded by the Ocean Park Conservation Foundation (OPCF), Hong Kong. OPCF is an organization committed to advocating, facilitating and participating in effective conservation of Asian wildlife, with an emphasis on Chinese white dolphins and giant pandas as well as their habitats. This is achieved through partnerships, fundraising, research and education. OPCFHK has allocated over $34 million to fund over 290 research projects on cetaceans, giant pandas and many other species since its expansion in 2005. www.opcf.org.hk/en/

We conduct research aimed at developing assisted reproductive technologies for at-risk amphibian species.

Congratulations to MSU undergraduate student and presidential scholar, Lindsay Culpepper, on winning first place oral presentation at the January 2022 International Embryo Transfer Society (IETS) meeting for her talk on impacts of different culture media during early embryonic development in amphibians. Lindsay is currently a Conservation Physiology Lab Undergraduate Research Scholar.